Scroll or skip down to individual sections:

- Unit 1: Listening Carefully (Carsten Wergin)↓

- Unit 2: Looking at the ordinary – a tender practice of forging relationships (Tania Katzschner) ↓

- Unit 3: Radical Hope in Turbulent Times: sources of inspiration from politics to poetry (John Barry) ↓

- Unit 4: The Rise of Optimism in the Conservation Movement (Elin Kelsey)

- Unit 5: Expecting the Unexpected—The Role of Art in the Dissemination of Radical Hope (Patrick J. Reed) ↓

- Unit 6: The Art of Protest: Radical Hope Envisioned and Embodied (Amy Hay) ↓

- Unit 7: Recurring Earthquakes and the Rebirth of Hope (Sophia Kalantzakos) ↓

- Unit 8: Infrastructures of Hope (Erika Bsumek) ↓

- Unit 9: Air Pollution: Issues and Solutions (Hal Crimmel) ↓

- Unit 10: Thrifty Science (Simon Werrett) ↓

- Unit 11: Planting seeds of hope: Environmental Education for the Present & future (Kieko Matteson) ↓

- Unit 12: Environmental Security: The Courage to Fear and the Courage to Hope ( Allan W. Shearer) ↓

- Unit 13: Look Down for Hope – Phytoremediation in an Italian Steel Town (Monica Seger) ↓

- Unit 14: Living In Good Relation with the Environment: A Syllabus of Radical Hope (Alina Scott) ↓

- Unit 15: On Love and Property (Kara Thompson) ↓

- Unit 16: Design, Hybridity and Just Transitions (Damian White) ↓

- Unit 17: The Answer is Blowing in the Wind: Grassroots Technological Networks of Wind Energy (Kostas Latoufis; Aristotle Tympas ) ↓

- Unit 18: Storytelling, Narrative, and a Just Transition ↓

- Unit 19: Direct Democracy of Medha Lekha Village ↓

Unit 1: Listening Carefully

Carsten Wergin

In this contribution, I draw on entangled ethnographic moments recorded in October 2015 in Heidelberg (Germany) and May 2017 in the Kimberley region in Northwest Australia. I argue that respectful and careful listening (to others) is a crucial skill through which to inspire radical hope. Commonly rendered invisible by an overemphasis on representationalism, in particular ill-defined ‘opportunities’ for economic development, my aim is to bring to the forefront practices of sonic engagement with/in the world as significant performative means to counter large-scale industrialization proposals.

How do you define radical hope?

As that which can stem from (radical) collaboration and co-becoming fostered by listening carefully.

How do you see radical hope emerging or playing out in your case study?

- In the truths of myths and storytelling that contest the dwelling of allegedly objective matters of fact,

- In the sonic intra-actions of diverse collaborators and their value regimes that hint towards new forms of onto-epistemic partnership.

In the video below I speak about how to address these issues ethnographically, with reference to my work in the Kimberley (Northwest Australia):

- Carsten Wergin (2017) How Can Australian Indigenous Experience Change Western Perspectives of the World? Latest Thinking (Open Access Video Journal), LT Video Publication, DOI: https://doi.org/10.21036/LTPUB10513

- The film Naji (2015) is set at the Kimberley coast and shares a story about Bugarrigarra (Creation Time) in Northwest Australia

Selected Readings

- Carsten Wergin (2016) Dreamings Beyond ‘Opportunity’: The Collaborative Economics of an Aboriginal Heritage Trail. Journal of Cultural Economy 9 / 5: 488-506. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2016.1210532

- Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing (2015) The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, Princeton University Press.

- Elizabeth Povinelli (2016) Geontologies: A Requiem to Late Liberalism, Duke University Press.

- Jonathan Lear (2008) Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation, Harvard University Press.

- Barad, K. (2007) Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning, Duke University Press.

BACK TO TOP ↑

Unit 2: Looking at the ordinary – a tender practice of forging relationships

Tania Katzschner

We live in truly perilous times with rapidly worsening social and ecological conditions. It is not difficult to feel deep despair as we gaze upon the world we currently inhabit. Although we are surrounded by plans, solutions, a sense of urgency, sometimes outrage, intentions, critiques, protests, and ‘wars’ on everything, we are somehow failing to meet the growing world crisis at social, political, economic and environmental levels. This paper, and corresponding section, explore how to inspire actionable hope and avoid propelling the same old patterns into the future and how to go beyond the questions of the present.

This moment poses challenges for which we possess neither effective knowledge nor adequate practices. In this context of crises, the promise of modernization no longer appears persuasive and our universal ‘one-world’ world is being challenged with an unprecedented degree of publicity for the first time and this paper argues that this possibility needs to be cared for. This moment invites us to create the means for posing problems differently.

This section of the course attempts to do this by reflecting on the practices and sensibilities of a transformative urban nature project in Cape Town. The project risked slowing down to nurture profound levels of observation and conversation in order to protect capabilities for flourishing. The project created spaces for competing ideas, discussion, and debate and helped create conditions where anything could happen, especially that which is beyond our limited knowledge of cause and effect.

This section searches for the art of fostering possibilities and argues that the art of paying attention must be reclaimed to nurture well-being and in order to work towards a more life-sustaining world.

How do you define radical hope?

Seeing success as elusive practices such as conversation and relationship rather than infrastructural and material changes.

How do you see radical hope emerging or playing out in your case study?

Different ways of being together is called for. This is a fundamental change in order to meet what is coming towards us. This shift in quality also emerges from the insistence on the idea of ‘practice’ instead of ‘guidelines’ or ‘models’. Radical hope is also about resisting the constant need for intervention – but rather embracing aspects of the uncertain.

The case study depicts the practices and sensibilities of a transformative urban nature project in Cape Town. The projects moves forward not with the aim of finding solutions but with the aim of understanding problems. It pays attention to the ordinary everyday and works towards a delicate subtle activism.

Readings, videos, movies, artwork

- Eisenstein, Charles, “This Is How War Begins” – Nov 2016

- Haraway, D (2010) ‘When species meet: Staying with the trouble’, in Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, volume 28, number 1, pp 53-5.

- Donna Haraway lectures at the San Francisco Art Institute, April 25, 2017.

- ‘Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene’

- Joint Visiting Artists and Scholars and Graduate Lecture Series Event

- Kaplan, A and S Davidoff (2014) A Delicate Activism- A Radical Approach to Change, published by the Proteus Initiative

- Katzschner T (2013) ‘Cape Flats Nature: Rethinking Urban Ecologies’ in L. Green (ed) Contested Ecologies : dialogues in the south on nature and knowledge, Cape Town: HSRC Press.

- Layne, T (2013) ‘Ordinary Magic: The Alchemy of Biodiversity and Development in Cape Flats Nature’ in SOLUTIONS for a sustainable and desirable future, Volume 4, issue 3, pp 84-92.

- Paddock, T (2015) ‘Is Democracy an Enemy of Nature?’, Organisation Unbound, January 2015.

- Stengers, I (2014) ‘Gaia: The urgency to think and feel’.

BACK TO TOP ↑

Unit 3: Radical Hope in Turbulent Times: sources of inspiration from politics to poetry

John Barry

WB Yeats, ‘The Lake Isle of Innisfree’

I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made:

Nine bean-rows will I have there, a hive for the honey-bee;

And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping

slow,

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket

sings;

There midnight’s all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet’s wings.

I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart’s core.

Hope Is The Thing With Feathers, Emily Dickinson

‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers—

That perches in the soul—

And sings the tune without the words—

And never stops—at all—

And sweetest—in the Gale—is heard—

And sore must be the storm—

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm—

I’ve heard it in the chillest land—

And on the strangest Sea—

Yet, never, in Extremity,

It asked a crumb—of Me.

In the turbulent times we live in and the uneven and unjust production and experience of social, economic and ecological harms, hope in all its manifestations is both available (if we look hard enough for it) and much needed.

How do you define radical hope?

The inspiration behind this workshop, and my own interest and work on ‘radical hope’ is based on that concept which came across almost a decade ago when I first read Jonathan Lear’s remarkable book, Radical Hope. In that book, Lear outlines a peculiar human vulnerability, one which all papers touch upon in different ways. As Lear puts it

“We seem to acquire it [this vulnerability as a result of the fact that we essentially inhabit a way of life. Humans are by nature cultural animals: we necessarily inhabit a way of life that is expressed in a culture. But our way of life –whatever it is– is vulnerable in various ways. And we, as participants in that way of life, thereby inherit a vulnerability. Should that way of life break down, that is our problem” (2006: 6).

This leads him, and us, to a troubling existential blind spot within (most) human cultures “the inability to conceive of its own destruction and possible extinction” (2006: 83). This means, for example, that we do not typically prepare our younger generation to consider or to prepare for the possible eventuality of our way/s of life, the terms and practices we use to render such ways of life, of common goods etc. to be vulnerable, so vulnerable they might, someday disappear completely. This ‘ontological insecurity’, to paraphrase Anthony Giddens, is not something we usually or usually willingly do. It is speculative (it may not happen, so why worry about it?), it is worrying and disturbing – hence thinking about possible futures might compromise one’s enjoyment of their present), and even if there are troubling times ahead human ingenuity, improvisation and resilience coupled with technological innovation will ‘take care of it’. Radical hope for me is not the same as optimism. As Vaclav Havel so perceptively put it “Hope is definitely not the same thing as optimism. It is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out”.

In this way ‘radical hope’ is a clear eyed recognition of the problems we face, a courageous and explicit disavowal of the temptations of a naïve (and at times dangerous) assumption that ‘all will be well’, but nevertheless a belief in the capacity of human agency. Hope, as Emily Dickinson, put it “is the thing with feathers”. Or as Lear notes, “What makes this hope radical is that it is directed toward a future goodness that transcends the current ability to understand what it is. Radical hope anticipates a good for which those who have the hope as yet lack the appropriate concepts with which to understand it” (2006: 103).

How do you see radical hope emerging or playing out in your case study?

Politically, my main area of interest and concern, there is much work to be done in establishing a critical, inspiring and realistic ‘infrastructure of hope’ which I view as allowing for a dialogue around new ideas about we organise the economy, conceive of a ‘good life’, reconfigure our democratic politics and so on. In the realm of ideas and the politically feasible there is a crying need for unleashing creativity and rethinking and repurposing established ways of ideas, practices and frames of reference. Our crisis is as much a crisis of creativity as it is a crisis of capitalism, the decline in a belief in collective change, climate change and so on. Such a creative dialogue to establish an ‘infrastructure of hope’ calls for public i.e. political debate and hybridisation and interdisciplinary cross-pollination between science, technology, philosophy, ethics, with participants from faith communities, those of no faith, citizens, experts, civil servants, business, trades unions, teachers, academics and students and many more besides. In short, radical hope and the creation of an infrastructure of hope may call for something akin to a new Renaissance or Enlightenment. A new Enlightenment however based more on modesty and critical self-reflection than the often bullish and arrogant anthropocentrism of ‘the Anthropocene’. Radical hope in our turbulent times I would suggest calls us to reflect less on how we as a species can control or manage the planet, to ‘take hold of the tiller of creation’ as Teilhard de Chardin put it. Perhaps it calls us to manage that for which we need no new technology or science, to manage not the planet or the more that human world, but rather to manage our relationships (both material-metabolic, conceptual and moral) with the earth, its entities and processes. And, while the reappraisal of our relationships is a quintessentially political act, and thus ‘radical’ in the Latin sense of ‘getting to the root’ of the problem, the sense of hope outlined here is radical in another sense.

This is the sense of hope as an antidote to the dangers (or comforting temptations) of what can be a debilitating negativity in forensically detailing all the problems of the current time. Hope here is a virtue guarding against the political and intellectual vice of dwelling in a self-righteous negativity, to ‘curse the dark’ but without also ‘lighting a candle’ for fear of being seen (or self-regarded) as naïve, politically or ideologically motivated or even ‘utopian’. Here what makes this hope radical is in the sense that Raymond Williams so aptly put it:

“To be truly radical is to make hope possible,

rather than despair convincing”.

Readings:

- Sharon Astyk (2008), Depletion & Abundance: Life on the New Home Front (New Society Publishers).

- Vaclav Havel (1985), The Power of the Powerless (London: Routledge).

- Vaclav Havel (1986), Living in Truth (London: Faber and Faber).

- Rob Hopkins (2008), The Transition Handbook: From Oil Dependency to Local Resilience (Totnes: Green Books).

- Gerry O’Hanlon SJ (ed) (2017), A Dialogue of Hope: Critical Thinking for Critical Times (Dublin: Messenger Publications).

- Pope Francis (2015), Laudato ‘Si: Care for our Common Home

- Jonathan Lear (2008) Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation (Harvard University Press).

- Alastair McIntosh (2004), Soil and Soul: People Versus Corporate Power (Aurum Press)

- Susan Sontag (1978), Illness as Metaphor, (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux).

- Raymond Williams (1989), Resources of Hope: Culture, Democracy, Socialism (London: Verso).

- The poetry of William Butler Yeats and Padraig Kavanagh

- Marvin Gaye’s 1971 album – What’s Going On

- Henryk Górecki’s Symphony No. 3: Symphony of Sorrowful Songs

- Dr. Seuss’ The Lorax

BACK TO TOP ↑

Unit 4: The Rise of Optimism in the Conservation Movement

Elin Kelsey

Paper: Crowd-sourcing hope and cultivating interspecies relationships in the Age of the Anthropocene and the Digital Revolution

The Digital Revolution is unleashing new understandings about life on Earth that rival the impact of the 15th Century discoveries of Columbus and Magellan (Arts, van der Wal & Adams, 2015). This new wild world is not the passive, subservient, humans-at-the-top version described in Aristotle’s great chain of being (Henning, 2014). It is a world where humpback whales use their social networks to improve their populations’ recoveries and mother trees distribute their energy across their root networks to improve the resilience of the forest. It is a world filled with the capacity to act and interact. And all that action and interaction creates resiliency in circumstances we might never have imagined.

Yet environmental news in mainstream media continues to be overwhelmingly reported as “bad news.” (Project for improved environmental coverage, 2015; McCluskey, Swinnen & Vandemoortele, 2015). And, doom and gloom remains the de facto environmental narrative not only for the ways in which we communicate environmental issues but also for the ways in which a range of environmental disciplines frame their fields of study. Environmental issues are real and horrific. But failing to separate the urgency of environmental issues from the fear-inducing ways we communicate them, blinds us to the collateral damage of apocalyptic storytelling. Hopelessness undermines the very engagement with environmental issues we seek to create.

In this paper, I describe the rise of optimism in the conservation movement. In 2014, I co-launched a twitter tag in an effort to crowd source and share examples of hopeful conservation successes (Kelsey, 2016). #OceanOptimism reached more than 75 million people in its first two years. It continues to spread across instagram, snapchat and other social media platforms and has sparked new campaigns for #EarthOptimism, #ConservationOptimism, #ClimateOptimism and more. This groundswell of optimism is sweeping through the global environmental community and has been embraced by leading public institutions including the Zoological Society of London and the Smithsonian Institution.

The rise of optimism embodies a revolutionary appreciation of the active capacity of other species and ecosystems to heal. Not in the superficial, “the earth will heal itself” rhetoric that abdicates human responsibility, but through a far-reaching recognition of recent breakthroughs in the study of the cognitive, social, emotional, and cultural experiences of other species.

How do you define radical hope?

I contend that it is not hope that is radical in the Age of the Anthropocene. What is radical is seeking to topple anthroparchy and its deeply entrenched belief in the superiority of humans over other species. Recognizing agency and self-efficacy in the other-than-human world, and creating sustainability practices and policies that amplify this collective capacity for resilience is fraught and radical – and long overdue.

How do you see radical hope emerging or playing out in your case study?

Life in the Anthropocene demands an embrace of the complexity, specificity and ambiguity of inter-species relationships. It challenges us to include the nonhuman world in pressing political, social, economic and cultural issues (Holm and Taffel, 2016). The most recent estimate puts the total number of species living on planet Earth at 8.7 million (Mora et al, 2011). These millions of species are active participants in the world. They drive resilience and recovery.

In this case study I argue that social networks – in both human digital and non-human cultural contexts – hold promise for sourcing and spreading conservation solutions which in turn beget hope.

Readings/Resources:

- Elin Kelsey giving a keynote on Wild Contagious Hope at the UN Life Below Water conference in Malmo, Sweden October 2017

- Read how others feel about hope and the environment on this exhibit created by the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society.

- Follow #OceanOptimism on twitter, Instagram, Facebook or snapchat

- Watch this TED talk by Suzanne Simmard about how trees talk to each other through social networks

- Watch this video on the capacity of whales to change climate

- Read (or listen) to this article on humpback whales and compassion

- Read this editorial on emotions and environmental education from the Canadian Journal of Environmental Education Vol 21 (2016)

- Watch this interview on hope and the environment with Elin Kelsey on The Green Interview.

- Earth Optimism Website

BACK TO TOP ↑

Unit 5: Expecting the Unexpected—The Role of Art in the Dissemination of Radical Hope

Patrick J. Reed

In my artworks-on-paper, I use collage to demonstrate a subversive model for inclusive, non-hierarchical, non-subjugating modes of social and environmental consciousness. I rely on this fundamentally anarchic and queer aesthetic tradition for its ability to amalgamate and ally incongruities in profoundly unexpected ways.

The motivations behind my creative endeavours are jointly informed by two lines of thought.

One is Ben Nicholson’s notion of “collage thinking” as proposed in his book Appliance House from 1990, in which he wrote “Collage is part of everyone’s experience and, however well it is understood, it seems to refer to a group of ephemeral things brought together by a logic that disturbs, or negates, the status of the individual elements.” The other is Timothy Morton’s concept of “dark ecology,” in which all things have the potential to coexist in an exquisite state of bittersweet bliss and “pain without suffering,” a state of mind that is erotic, spiritual, and particularly attuned to collusions of the biosphere.

Collage, and by extension collagist thinking, promotes an uncomfortable balance that is applicable in an ecological dimension and has the potential to be radically more open and ethical as a mindset than the attitude of comfortable imbalance that is pervasive among the late late capitalism of the West—and therein lies the hope.

How do you define radical hope?

Radial hope is the willingness to accept and initiate radical empathy, radical capacity, radical partnership, and the radically unforeseen with the hope the one has the strength to do so.

How do you see radical hope emerging or playing out in your case study?

This project is my contribution to the campaign of radical hope as I have defined it above. My artworks demonstrate the ecological implications of collage, and function as catalysts for engaging others in contemplating the queer ontological shift engendered by collage thinking.

Readings and Resources (that exhibit or are sympathetic to the possibilities of collage thinking):

- Bourriaud, Nicolas. Relational Aesthetics. Paris: Les Presse Du Reel, 1998.

- Burroughs, William S. Naked Lunch. New York: Grove Press, 1992.

- Cage, John. 4’ 33”. Leipzig: C.F. Peters Ltd. & Co. KG, 2012.

- Cage, John. Litany for the Whale. Leipzig: C.F. Peters Ltd. & Co. KG, 1980.

- Caulfield, Sean. The Flood, 2016. Hand-carved woodblock panel. 6 x 9 m. Edmonton, Alberta, Art Gallery of Alberta.

- de Maria, Walter. The Lightning Field, 1977. Land art work. 1 mile x 1 kilometre. Catron Country, New Mexico.

- Morton, Timothy. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World.Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

- Scriabin, Aleksandr. Mysterium, 1903-1915. New York: G. Schirmer, Inc. 1915.

- Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. London: Penguin Classics, 2003.

- Solaris. Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky. 1972. New York: The Criterion Collection, Inc., 2002. DVD.

BACK TO TOP ↑

Unit 6: The Art of Protest: Radical Hope Envisioned and Embodied

Amy Hay

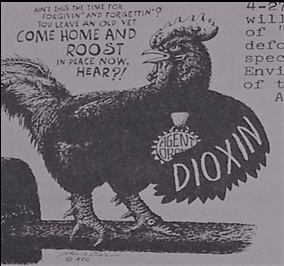

Some of the visual texts examined include the scribbled pictures in the meeting minutes of an ecumenical group formed to protest state inaction. The doodle showed various individuals as puppets, and included scientists and public officials, and in the process reveal a particular understanding of the world. One group used a striking picture of a young child getting their blood drawn in a fundraising letter and in the process identified the state as the enemy. Another environmental activist used striking visuals for the letterhead of her monthly newsletter. Sometimes there were dancing demons or dioxin-labeled chickens that had come home to roost. An examination of such visual texts offers important understandings of the ways activists effectively frame and challenge scientific and state authority while at the same time offering a different entry point, and potentially a more positive one, for us to understand difficult and unpleasant issues connected to environmental degradation and catastrophe.

Activism represents an especially important recovery project, not only because activists persevere in the face of significant and often depressing obstacles, but because meaningful change frequently happens incrementally, obvious only in hindsight. While many environmental social movements appeal to emotion and morality, they also ground themselves in the lived experience. Thinking about the things that sustain social movements offers hope in times when an individual or group may be a solitary voice in the wilderness, or when such forces transform society. We all may need to practice the art of protest as we address the realities of environmental loss and need for resilience and recovery.

How do you define radical hope?

Hope that nurtures change, often in the face of daunting opposition. Activists work to make change happen, and visual images and rhetoric offer one way to measure their hopes, fears, understandings, and determination.

How does radical hope emerge from my case study?

The various visual texts produced by environmental activists represent activists’ awareness, critiques, and humor as they pursued challenges to entrenched power. These texts often embody the idea of radical hope – a consciousness and commitment to determination, perspective, righteous anger, and biting humor while engaged in changing society and the world. Examining the materials produced by anti-toxic activists, an understudied area of environmental protest, provides a lens by which to understand the visual culture of protest and the emotional state(s) which sustain them.

Required Texts (Readings, Images, and Film):

- Thomas W. Benson, excerpt, Posters for Peace: Visual Rhetoric and Civic Action (Pennsylvania Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, reprint, 2015).

- Linda Gordon, “Dorothea Lange: The Photographer as Agricultural Sociologist,” The Journal of American History, 93, No. 3 (Dec., 2006), 698-727.

- [Gordon examines the work of noted photographer Dorothea Lange during the Great Depression. Lange’s photographs captured the effects of the economic crisis in rural America and made an argument for government intervention.]

- James M. Jasper, “The Emotions of Protest: Affective and Reactive Emotions in and around Social Movements,” Sociological Forum, 13, No. 3 (Sep., 1998), 397-424.

- [Jasper discusses the centrality of emotions to collective action and protest.]

- Nicolas Lambert, A People’s Art History of the United States: 250 Years of Activist Art and Artists Working in Social Justice Movements (New York: The New Press, 2015).

- T.V. Reed, “ACTing UP Against AIDS: The (Very) Graphic Arts in a Moment of Crisis,” in The Art of Protest: Culture and Activism from the Civil Rights Movement to the Streets of Seattle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005).

- Rebecca Solnit, Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities (Chicago, IL: Haymarket Press, 2015).

- Ralph Young, Make Art Not War: Political Protest Posters from the Twentieth Century (New York: New York University Press, 2016).

- DamNation (2014) – Documentary Film: Activists focused on river and wetland restoration make a film about America’s “deadbeat” dams. These are dams that no longer serve the function for which they were built and which now disrupt and destroy local ecosystems. The documentary provides a historical overview, interviews with activists, and contemporary encounters in advocating that these dams be removed and watersheds restored.

- Finis Dunaway, Seeing Green: The Use and Abuse of American Environmental Images (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015)

- 1971, “Crying Indian,” Public Service Announcement

BACK TO TOP ↑

Unit 7: Recurring Earthquakes and the Rebirth of Hope

Sophia Kalantzakos

Abstract: In April 2015, a devastating earthquake struck Nepal killing over 8,000 people and injuring more than 21,000. It erased whole villages at the foothills of the Himalayas, razed ancient cultural moments at UNESCO World Heritage sites. It devastated infrastructure and disrupted the way of life of one of the poorest countries in the world. In this paper, I examine diverging responses to this disaster that has left the country reeling under the burden of reconstruction in the midst of political turmoil. These responses serve as contrasting paradigms for cultures facing destruction in the Anthropocene.

Specifically, one rooted in historical Nepalese culture and memory represents a story of resilience and hope, where communities came together autonomously to celebrate life and hope of renewal. Citizen-led initiatives helped catalogue the destruction of the temples and cultural monuments and encouraged farmers to plant their crops so that they could have food (and not rely on foreign aid) in the months after the harvest.

The other technocratic, bureaucratic, and political response by the global institutions in concert with the central government once again proved the systemic inefficiencies governing international aid in a time of disaster. Nepalese know that earthquakes in their country are inevitable, happen with regularity – though many decades apart – each time bringing down vestiges of their culture, and their lives. Yet, this recurring experience so familiar and painful also calls for them to start anew reaffirming their radical hope in the future of their people. This paradigm becomes particularly telling especially in the Anthropocene and in the face of the growing climate crisis. Nepalese resilience provides a hopeful message for the future.

How do you define radical hope?

Radical hope is embracing the temporal and celebrating the intangible. It’s not wanting to check off another item from a long to-do list and think we are done with a problem which can then safely be put away and forgotten. Radical hope is knowing that change is constant; it’s wanting to build community; refusing to be alone and isolated; from the world, from oneself, from nature. It’s not being resigned to the inevitable but more importantly of believing that it’s meaningful and significant to act. Giving up the need to dominate will offer notions of radical hope in the Anthropocene.

How do you see radical hope emerging or playing out in your case study?

I found it inspiring that one of the poorest nations in Asia did not yield under the devastating earthquake of 2015. Instead, through community, heritage, traditions and spiritual beliefs it mobilized with dynamism and intent to restore its monuments, its faith, its home and its economy. In a country that has had to rely on its own society for decades, where government has largely been an impediment and certainly not a source of solutions, the Nepali people have proven resilient, creative, hands-on and optimistic. Earthquakes are recurring in Nepal, it’s part of the country’s psychic experience and yet, they plan with an eye at rebuilding again and again. What matters is passing down the knowledge from generation to generation so that the chain of memory, expertise, and resilience is unbroken. Radical hope resides in the Nepali outlook, community and spiritual bonds that keep people grounded and connected over time.

Readings/Resources

These readings and resources represent a wider thinking about Radical Hope. While they do not all touch upon Nepal’s hopeful recovery and spirit, they do contribute to the wider discussion of what radical hope might look like in the Anthropocene. They weave narratives of resilience, action, and rebirth ahead of the growing challenges ahead.

Readings:

- Bandyopadhyay, Tarashankar. The Tale of Hansuli Turn. Translated by Ben Conisbee Baer. Place of publication not identified: Columbia University Press, 2016.

- Francis, Pope. Laudato Si — On Care for Our Common Home. Our Sunday Visitor, 2015.

- Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower, An opera by Toshi Reagon and Bernice Johnson Reagon.

- Nick Papandreou, The Magical Path to the Acropolis, Melissa Books, 2017

- Flight of the Butterflies, by director Mike Slee. http://www.flightofthebutterflies.com/the-story/

- Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Return to Nepal: Rise of the Artisans

- The National Trust for Nature Conservation

BACK TO TOP ↑

Unit 8: Infrastructures of Hope

Abstract: This section of the syllabus looks at different approaches to infrastructure in America and considers what a study of large scale infrastructure projects might tell us about sustainability, environment, and hope. Readings focus on the ways in which politicians, architects, engineers, urban planners, naturalists, environmentalists, and others approached and thought about the relationship between infrastructure and social development – and how, in turn, the land and peoples’ relationship to it (and each other) were transformed in the process. An examination of hard infrastructures, like dams, can be juxtaposed with that of the “soft” infrastructures of education and government. Readings are meant to help participants explore the relationship between hard and soft infrastructures and think about how studying both may yield new solutions to older environmental problems. Some of the readings illustrate that the engineers who designed such projects were not short on hope. Yet, a number of the projects those engineers designed have also transformed nature in sometimes profoundly negative ways. The goal, moving forward, is to avoid such an outcome by asking readers to consider how we might construct “infrastructures of hope” in response to environmental crises.

How do you define radical hope? The continued act of questioning what is best for the environment and how humans can sustainably interact with it. This includes learning from the past in a way that fosters a persistent ability to think about the how present day problems can be solved without, hopefully (!), creating new environmental problems in the future.

How do you see radical hope emerging or playing out in your case study? First and foremost, I am not a techno optimist. Nor am I a techno-pessimist (as Leo Marx defines them). Instead, I think we need to take a hard look at the relationship between technology, the environment, and political, social, and cultural relationships in the United States over the course of the 20th century. I also think there is inherent value in looking to the past to understand what techo-optimsits, engineers, urban-planners, and industrialists were thinking (and what they ignored) when they designed our roads, highways, dams, electrical grids, cities, and suburbs. The plans they made — and projects they built — have deeply influenced our not just the way Americans think about infrastructure (i.e. the built environment) but also how specific “soft” infrastructures either facilitated and/or sometimes pushed back against seemingly unbridled techno-optimism (i.e. how did environmental organizations, educational institutions, legal institutions, financial institutions, governmental entities, etc. respond to large scale projects). Resource management, while seemingly a practical matter, is key to any functioning society.

Looking to understand the history of infrastructure also helps us see how society has been consciously built and organized in accordance with dominant views on race, ethnicity, class, and gender.

Looking at the relationship between hope (which is inherently future oriented) and infrastructure (who dominates our daily lives and shapes our future) forms the basis of this unit.

Readings/Resources:

- Richard C. Bradley, “Is Engineering Education Enough?” A Paper presented at the 70th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Engineering Education; U.S. Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs, Colorado; June 18 to 22, 1962) Primary source.

- Documentary Tó éí ííńá át’é: Water Is Life

- David Brower, “Let the River Run through it”

- Companion: Listen: Floyd Dominy

- Jared Farmer, “Glen Canyon and the Persistence of Wilderness,” in WHQ (Summer 1996); 210-222.

- http://engl273g-s12-stamatel.wikispaces.umb.edu/file/view/pdf+Glen+Canyon+and+Edward+Abbey.pdf

- Andrew Needham, Power Lines: Phoenix and the Making of the Modern Southwest, (Princeton University Press, 2016).

- Companion short reading: Erika Bsumek and Betsy Frederick Rothwell, “Stop Trying to Control Nature,” Time Magazine, April 22, 2016.

- Josh Lewis, “Ecological Checkpoints,” Issue 10, April, 2018.

- Darin Wahl, “Rethinking Cities as Vulnerable Ecosystems”

- Henry Petroski, To Engineer is Human: The Role of Failure in Successful Design (Vintage, 1992).

- Erika Bsumek, “Eco-Images: Imagining Indians and Revising Reclamation Debates,”

- Dana Powell, Landscapes of Power: Politics of Energy in the Navajo Nation (Duke University Press, 2018)

- Amy Slaton, Race, Rigor, and Selectivity in U.S. Engineering: This History of an Occupational Color Line (Harvard University Press, 2010).

- Tom Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: RAce and Inequality in Post War Detroit (Princeton University Press, 2014).

- –Companion resource: Real Estate and Race: Read the information on the website and explore the maps. Detroit Redlining

- Kyle Shelton, Power Moves: Transportation, Politics, and Development in Houston (University of Texas Press, 2017)

- Ted Steinberg, Down to Earth: Nature’s Role in American History (Oxford University Press, 2009).

Chris Wells, Car Country: An Environmental History (University of Washington Press, 2014) - Companion primary documents to Shelton and Wells: –“On the Interstate” from Smithsonian exhibit America on the Move

- “Eisenhower Interstate Highway System Home Page.”

- Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum.

- McKinnon, Catriona. “Climate Change: Against Despair.” Ethics and the Environment 19, no. 1 (2014): 31-48. doi:10.2979/ethicsenviro.19.1.31.

Select Blogs and Websites:

- Stanford, Spatial History Project

- American Society for Civil Engineers

- “Exhibitions — FORM and LANDSCAPE.”

- “Living New Deal.”

- “The Center for Land Use Interpretation.”

- “BLDGBLOG.”

- “99% Invisible.”

- City Lab

- “Paleofuture.”

BACK TO TOP ↑

Unit 9: Air Pollution: Issues and Solutions

Hal Crimmel

Abstract: Since the dawn of the industrial area, air pollution has been a stubborn problem, especially in crowded urban areas. Air pollution in London and other European cities, for example, steadily worsened during the 1800s as the tonnage of coal being burned to power industry and generate electricity grew. But the most infamous air pollution event not attributable to a single event, such as Chernobyl, or the 1984 Bhopal, India, disaster caused by a Union Carbide pesticide plant’s release of thirty tons of toxic gas, took place just over sixty years ago. In December 1952, a combination of unusual weather patterns and the burning of low-grade coal caused the Great Smog of London, an event which killed thousands and led to new clean air laws in Britain. In the United States, the October 1948 Donora Smog was and remains the worst short-term air pollution-related disaster in the nation’s history, where airborne pollutants from local steel mills became trapped in the valley, killing at least twenty people and sickening thousands more.

Today, the World Health Organization estimates that 92% of the world’s population lives in areas where air pollution exceeds WHO limits; nearly 1 out of 9 deaths globally—some 10 million—are attributed to poor air quality, an environmental issue of global concern. In the United States, the American Lung Association estimates that nearly half of all Americans live in areas with compromised air quality, from Fairbanks, Alaska, to Los Angeles, from the Central Valley of California to New York City and on up to rural Maine. An MIT study estimated the number of premature deaths attributable to air pollution in the United States at 200,000. Indeed, and without considering the impact of carbon pollution on the climate, air pollution has and continues to profoundly impact our environment.

This section uses a case study approach from my home state of Utah, which has one of the nation’s worst wintertime air quality problems and seeks to explore how sustainability transformations in the present, including those consisting of energy, mobility, and public policy, can produce meaningful improvements to air quality in concert with the role of realistic hope created by non-profits, individuals, communities and policymakers taking action to restore local and regional airsheds. In Utah, as elsewhere across the globe, public demands for action on air quality have been galvanized by the narrative of health, an important reframing that contrasts with the industrial and dominant political narrative, which focuses on how curbing air pollution impacts jobs and the economy. Most of the content from this unit comes from my forthcoming (University of Utah Press, 2019) book, Utah’s Air Quality Issues: Problems and Solutions.

How do you define radical hope?

I see it as a rejection of the notion that we can’t change the ways things are currently, and as an embrace of the idea that targeted efforts can result in meaningful changes.

How do you see radical hope emerging or playing out in your case study?

In the context of this project, I see it as a question of perception and of action. Unlike other environmental issues—toxic waste dumps or localized water pollution, for instance, air pollution impacts everyone in a particular place, though some more so than others due to proximity to pollution sources. But in general, unless one moves out of state, there is no escape during periods of moderate to severe pollution. Such realizations have spurred many here to do something about what can genuinely seem, during the most severe wintertime pollution episodes, apocalyptic and fully dystopic. Yet many here are committed to rejecting earlier narratives of helplessness—and in this regard, the movement to improve the state’s air quality evinces a certain hope that could provide a template for the future, here and in key locations around the globe. The health awareness the movement has raised, the research it has created, and the political will it has started to generate has and will result in regulations, legislation, stepped-up enforcement and changed citizen behavior–all parts of solving the air pollution puzzle.

Readings/Resources related to Utah

- Alexander, Thomas A. : “Cooperation, Conflict, and Compromise: Women, Men, and Environment in Salt Lake City, 1890-1930”. BYU Studies Quarterly 35 (1) 1995. 7-39.

- Crimmel, Hal, ed. Utah’s Air Quality Issues: Problems and Solutions. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2019.

Table of contents:

- Introduction: HAL CRIMMEL

- Chapter One: Breathing in Utah’s Parks and Protected Areas: Air Quality and the Visitor Experience. CHRIS ZAJCHOWSKI

- Chapter Two: What’s in the Inversion?: Particulate Matter Pollution in Northern Utah. KERRY E. KELLY

- Chapter Three: Ozone, Dust and Climate Change: Air Quality in Rural Utah. SETH ARENS

- Chapter Four: Air Pollution and its Impacts on Human Health. BRIAN MOENCH

- Chapter Five: Air Pollution Control in Utah–The Legal Framework. JAMES A. HOLTKAMP

- Chapter Six: The Economics of Air Quality in Utah. THERESE C. GRIJALVA and MATTHEW GNAGEY

- Chapter Seven: Mobile Source Pollution and the Role of New Vehicle Technologies in Cleaning the Air. WILLIAM SPIEGLE

- Chapter Eight: Environmental Justice and Advocacy . MARK A. STEVENSON and DENNI CAWLEY

- Chapter Nine: Designed for Clean Air: The Role of Urban Planning and Transit in Solving Wasatch Front Air Quality Issues. ERIC C. EWERT

- Chapter Ten: Carbon Pollution and the Impacts of Climate Disruption on Utah

ROBERT DAVIES

Utah Websites:

- AirNow: Utah Air Quality (This site is maintained by the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and displays air quality across the United States. Users will find many helpful links.)

- Breathe Utah This site provides information useful for understanding air quality in Utah, including resources for getting involved in improving Utah’s air.

- Breathing Stories: Utah Voices for Clean Air

- Chapbook from Torrey House Press is a compilation of stories from citizens

- Utah Department of Environmental Quality: Air Quality

- The Utah Division of Air Quality is a state agency under the Utah Department of Environmental Quality. Users will find many useful links.

- Utah Physicians for Healthy Environment (UPHE)

- This organization was founded by physicians and “is dedicated to protecting the health and well-being of the citizens of Utah by promoting science- based health education and interventions that result in progressive, measurable improvements to the environment.

Other air-quality resources for consideration: - Davis, Devra. When Smoke Ran Like Water: Tales Of Environmental Deception And The Battle Against Pollution. New York: Basic Books, 2003.

- When Smoke Ran Like Water, written by a well-known epidemiologist, is written in narrative format, and provides “insights into the science and politics of public health.” As such it is something of an exposé of how industry has fought efforts to control many forms of environmental pollution. The book covers such topics as the battle to remove lead from gasoline, the effects of pesticide exposure on workers, the links between trichlorolethylene and cancer, and the effort in the 1970s to require the installation of pollution control devices on automobiles, among other topics.

- Dewey, Scott Hamilton. Don’t Breathe the Air: Air Pollution and U.S. Environmental Politics, 1945-1970. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2000.

- This book focuses on how air pollution became a social and public health issue in the 1960s. Using case studies from Los Angeles, New York, and Florida, the text discusses “how local efforts helped create both the modern environmental movement and federal environmental policy”.

- Steingraber, Sandra. “Air” in Living Downstream: An Ecologist’s Personal Investigation of Cancer and the Environment. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2010.

- Steingraber’s book contains one chapter on air pollution and its health impacts.

- Earth Under Siege: From Air Pollution to Global Change, Second Edition. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2002.

- This textbook “offers a comprehensive overview of environmental issues for students in the physical and life sciences, geography, economics, engineering, environmental management and law, policy studies, and social and health sciences.” It is extremely thorough, covering everything from basic physical and chemical principles to global environmental engineering.

- McGranahan, Gordon and Frank Murray, eds. Air Pollution & Health in rapidly developing countries. New York: Routledge/Earthscan, 2012.

- The edited collection Air Pollution & Health in rapidly developing countries targets “pollution and health policy-makers, researchers and others concerned with air pollution and health in developing countries.” In eleven chapters, this book reviews studies of air pollution from Africa, Asia, and South American and compares them with those originating in Europe and North America.

- Phalen, Robert F. and Robert N. Phalen. Introduction To Air Pollution Science: A Public Health Perspective. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2013.

- Introduction To Air Pollution Science is a textbook written expressly for “upper-level undergraduate and introductory graduate courses in air pollution”. It looks and reads like a textbook, though it contains quality information on the health impacts of air pollution.

- Vallero, Daniel. Fundamentals of Air Pollution, Fifth Edition. Burlington, MA: Elsevier, 2014.

- Fundamentals of Air Pollution is probably the best air pollution textbook on the market. Highly detailed and up-to-date on all aspects of air pollution, this 942-page book is targeted toward engineers and managers “tasked with the responsibility of air pollution control.”

BACK TO TOP ↑

Unit 10: Thrifty Science

Simon Werrett

Is expanding consumption and use of limited resources and energy an inevitability, or are there alternative ways of living that might lead to a more sustainable world? History offers hopeful solutions, and in this section we consider past practices and ideas concerning material things that understood them in very different ways to those prevalent in the industrialized world today. As Karen Harvey explains in her chapter “The Language of Oeconomy”, early modern writers in sixteenth to eighteenth-century Europe championed “oeconomy” or household management, which valued “thrift” and “frugality” in managing everyday affairs. Thrift was not understood as saving money but as finding a balance between buying new and making the best use of what one already owned. It also combined material and moral concerns, looking after possessions and people were connected and equally important. Thomas Tusser’s book of household tips provides fascinating evidence of this wide meaning of “thrift” in early modern England, revealing its connection to the optimistic notion of “thriving”. Inherent in thrifty living was a form of experimentation and creativity shared by men and women, who sought to “make use” of things as best they could. This was the heart of oeconomy and it could be argued was a major impetus to the rise of experiment as a way of knowing about nature in the seventeenth century. The chemist and champion of experimental method Robert Boyle’s essay “Of Men’s Great Ignorance of the Uses of Natural Things” makes this apparent, as Boyle wrestled to find new uses for a variety of mundane items and waste products in the service of good oeconomy. Women also experimented, finding out the uses of herbs and minerals to make medicines, as Leong shows. Thrifty householders made good use of things, and making things endure helped achieve this. Repair work, maintenance, careful storage and recycling all contributed to extending the lives of goods, areas whose history has been little studied thus far, though some aspects of these practices are examined by Werrett, Oldenziel and Trischler, Fennetaux, Vasset and Junqua. Continuous reworking of possessions into new uses meant that early moderns understood material things to be open-ended or “incomplete objects” capable of constant revision, an idea explored in a contemporary setting by Karin Knorr-Cetina.

How do you define radical hope?

Thrift, understood in its early modern sense of being a path to thriving, offers an alternative to the seeking after endless growth and exploitation of resources characteristic of modern economies. What I call “Thrifty science” consists of a myriad of small-scale, manageable practices for changing everyday life, learned from history, which serve as an alternative to grand but unrealistic ideologies for global environmental transformation. Oeconomic thinking also offers hope. While today’s economics tries to erase the human from the circulation of money and resources, reducing it to measures and numbers, oeconomics reintroduces the human and moral to these flows, investing people and things with importance requiring preservation and care. Oeconomics is a radical path to thriving.

How do you see radical hope emerging or playing out in your case study?

We don’t yet have even the beginnings of a science of oeconomics, but I have tried to begin exploring the idea in a paper entitled “Shiftspaces”. Shift is an early modern term for a clever improvisation, using what you have ready to hand to make something. It could be a scientific instrument made from coffee pots and clay pipes, or a container constructed from old china fragments or bottles. Shiftspaces, then, are places which are made from, and encourage the making of, shifts. They could be “maker spaces” or “hack spaces” of the kinds that have sprung up in recent decades, websites sharing knowledge, or repair shops, or just kitchens or sheds used for tinkering (see the links to Jugaad Innovation, Past Imperfect, the Library of Things, the Maintainers). Shiftspaces are laboratories for oeconomics, where radical hope emerges, where people and things learn to thrive.

Readings

- Simon Werrett, Thrifty Science: Making the Most of Materials in the History of Experiment (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019)https://www.press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/T/bo35612006.html

- Fennetaux, Ariane; Sophie Vasset and Amélie Junqua, eds., The Afterlife of Used Things: Recycling in the Long Eighteenth Century (New York: Routledge, 2014).

- Franklin, Benjamin. “The Way to Wealth.” In Anon. Miscellanies in Prose and Verse: Selected from Pope, Swift, Addison, Goldsmith, Sterne, Hume, Smollet, Gay, Shenstone, Prior, Murphy, and Brooke (Leominster, c. 1770), 61-72.

- Harvey, Karen, The Little Republic: Masculinity and Domestic Authority in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

- Knorr-Cetina, Karin, “Objectual Practice.” In The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory, edited by Theodore R. Schatzki, Karin Knorr-Cetina, Eike von Savigny (London: Routledge, 2001), 175-188.

- Leong, Elaine, “Collecting Knowledge for the Family: Recipes, Gender and Practical Knowledge in the Early Modern English Household,” Centaurus 55 (2013): 81–103.

- Oldenziel, Ruth, and Helmuth Trischler, eds., Cycling and Recycling: Histories of Sustainable Practices (New York; Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2016).

- Tusser, Thomas, Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry As Well For the Champion or Open Countrey… and Besides the Book of Houswifery (London, 1672; 1812 edition); xviii-xxi (“The Ladder to Thrift”).

- Van Driel, Joppe, “The Filthy and the Fat: Oeconomy, Chemistry and Resource Management in the Age of Revolutions.” PhD diss., University of Twente, 2016.

- Werrett, Simon, “Recycling in Early Modern Science.” British Journal for the History of Science 46 (2013): 627-646.

- Werrett, Simon, “Household Oeconomy and Chemical Inquiry.” In Compound Histories: Materials, Production, Governance, 1760-1840, edited by Lissa Roberts, Simon Werrett (Leiden: Brill, 2017), 35-56.

- Boyle, Robert, “Essay X. Of Men’s Great Ignorance of the Uses of Natural Things: or, That there is scarce any one Thing in Nature, wherof the Uses to human Life are yet thoroughly understood,” [1671] in Robert Boyle, The Works of the Honourable Robert Boyle, 6 vols. (London, 1772), vol. 3, 470-94.

Other sources

- An introduction to Jugaad Innovation

- Past Imperfect: The Art of Inventive Repair

- The Library of Things

- The Maintainers

- A very brief video on “thrifty science”

BACK TO TOP ↑

Unit 11: Planting seeds of hope: environmental education for the present & future

Kieko Matteson

Paper: “Artemisia’s Army: Environmental Education as Bioremediation”

Abstract: The news these days feels relentlessly grim on nearly every issue, from economic security to human rights to the ecological health of the planet. On the political front, cynics and strongmen exult in their increased influence, dismantling longstanding social and environmental protections with ever-increasing boldness and thumbing their nose at all who object. Politics as usual seem inadequate, but so too does resistance at the scale necessary to make a difference.

How, then to respond to the crises pressing in on all sides?

The best bet, I contend in this section of the syllabus, is environmental education. My essay looks at four diverse approaches spanning from elementary and middle school to university-level, each created by women whose earlier careers led them to a common conclusion: that the only way to make a genuine and lasting difference is to nurture children’s curiosity and foster compassion for the natural world. Planting the seeds of environmental engagement in every child is not for the faint of heart – it requires painstaking effort and the patience of Job – but taken collectively, the impacts are enduring and powerful.

Starting with my essay, this module invites students to consider the diverse motivations and methodologies of environmental education. Readings and other resources present different curricular approaches, while assignments (at the discretion of the instructor) should encourage students to explore the strengths and weaknesses of other models of environmental pedagogy.

My aim is to encourage students to think about the ways education can enhance or proscribe our relationships with the natural world. How might more unorthodox approaches from early childhood on up inspire wonder, foster greater awareness of non-human environmental stakeholders, and encourage more sustainable forms of resource use in the long and short run?

How do you define radical hope?

The most radical expression of optimism is slow hope, to borrow Christof Mauch’s expression – in this case, the pursuit of a pedagogy committed to cultivating change from the ground up, with the aim of creating a society of individuals culturally, intellectually, spiritually, and materially committed to caring for all the elements of the earth, animate and inanimate alike.

How do you see radical hope emerging or playing out in your case study?

The case studies I explore in my essay are the living embodiment of radical hope, in each woman’s bold efforts to devise an ethical, invigorating, creative curriculum that encourages young people to shake off the status quo and devise a more ecologically viable vision for the future.

Readings:

- Davis, Julie M. Young Children and the Environment: Early Education for Sustainability. 2nd ed. (Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

- Grant, Tim and Gail Littlejohn. Teaching Green: The Elementary Years: Hands-on Learning in Grades K-5 (Gabriola, B.C.: New Society Publishers, 2005).

- Locke, Steven. “Environmental education for democracy and social justice in Costa Rica.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 18:2 (2009) 97-110.

- Louv, Richard. Last Child in the Woods: Saving our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. (Chapel Hill, NC, Algonquin Books, 2005).

- O’Kane, Trish. “What the Sparrows Told Me.” New York Times, August 17, 2014, New York edition, p. SR6.

- Saylan, Charles, and Daniel T. Blumstein. The Failure of Environmental Education (and How We Can Fix It). (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011).

- Sobel, David T. Childhood and Nature: Design Principles for Educators. (Portland, Me., Stenhouse Publishers, 2008).

- Wake, Lynn Overholt. “E.B. White’s Paean to Life: The Environmental Imagination of Charlotte’s Web,” in S.I. Dobrin and K.B. Kidd, eds. Wild Things: Children’s Culture and Ecocriticism. (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2004), 101-114.

- Wattchow, Brian and Mike Brown. A Pedagogy of Place: Outdoor Education for a Changing World (Monash University Publishing, 2011).

Websites:

- Colleges of the Fenway (Massachusetts) Minor in Sustainability

- North American Association for Environmental Educators (see especially guidelines and workbooks for educators)

- SEEQS, School for Examining Essential Questions of Sustainability, Honolulu, Hawai`i. “Essential questions” curriculum

- Wilderness Education Association

Programs, videos, articles, and exhibitions featured in my essay:

- Collier, Andrée, TEDx theme “Joy and Purpose” October 3, 2015, Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts.

- Marris, Emma. Rambunctious Garden: Saving Nature in a Post-Wild World (Bloomsbury USA, 2011).

- Marsching, Jane. “Incubating Change: Pedagogies of Sustainability in Art and Design Education,” paper presented at the College Art Association conference, New York, NY, February 18, 2017. [PDF]

- Marsching, Jane, “Ice Out”

- Marsching, Jane, “Test Site”

- Marsching, Jane, “Water Quality Sing-Along”

- O’Kane, Trish. “Pattern of Migration,” New York Times Magazine, March 25, 2007.

BACK TO TOP ↑

Unit 12: Environmental Security: The Courage to Fear and the Courage to Hope

Allan W. Shearer

Can you imagine the collapse of a civilization? Smaller in scale, but perhaps more immediate, can you imagine the death of your own society? What attitudes and what skills are needed to do so? And, if you can do it, what can you do next to prevent the end from coming?

In 1962, during what can arguably be considered as the height of the Cold War, national security expert Herman Kahn encouraged “thinking about the unthinkable”: the use of thermonuclear weapons. That same year, peace activist Gunther Anders put forth the premise that society’s ability to fear was too small to match the magnitude of the dangers posed by weapons of mass destruction. In response, he called on people to expand their imaginations and have, “the courage to fear.” Perhaps the fact that two such very different people called for creating the capacity to imagine existential scenarios indicates a fundamental challenge to our cognitive capabilities. But if envisioning potential horrors is necessary to understand our vulnerability, it is not, however, sufficient. Action must follow. Anders knew that in the face of fear, people may run for cover. He wanted people to take to the streets. Although Anders di not say so explicitly, the courage to fear must be complemented by “the courage to hope”—to also envision desired possibilities that demand action in order to become realities.

Today, the threat of nuclear war persists, but it is often overshadowed by concerns that the combination of population growth, planetary urbanization, economic globalization, and climate change will result in ecological collapse, social strife, and personal suffering. In this context, what does it mean to have the courage to fear? What could it mean to have the courage to hope?

How do you define radical hope?

An image of the world and a design of action that brings about a future which offers more choices for people than they have today.

How does radical hope emerge from my case study?

By analogy, from the perspective that communities and cities can be understood as living systems, with the hypothesis that understanding the causes and conditions of illness and the causes and conditions of wellness are complementary, and through the examination of extreme cases.

Readings:

- Anders, G. (1962) “Theses for the Atomic Age,” The Massachusetts Review 3(3):493–505.

- Boulding, K.E. (1961) The Image: Knowledge in Life and Society. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Boulding, K.E. (1989) Three Faces of Power. London: Sage.

- Buzan, B., Waever, O., and de Wilde, J.. (1998) Security: A New Framework for Anaylsis. London: Reinner.

- Liotta, P.H. and Shearer, Allan W. (2007) Gaia’s Revenge: Climate Change and Humanity’s Loss, Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Morton, T. (2016) Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence, New York: Columbia University Press.

- Norton, R.J. (2003) Feral Cities, Naval War College Review 55(4):97–106.

- Shearer, A.W. and Liotta, P.H. (2010) Sustainability, Security, and States: Problems of Uncertainty, Paths of Action, in Wagner, C.G. (ed.) Strategies and Technologies for a Sustainable Future, 363–386, Bethesda, MD: WFS.

- Shearer, A.W. (2015) “Abduction to Argument: A Framework of Design Thinking,” Landscape Journal 34:2, pp. 127–138.

- Solnit, R. (2016) Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities, 3rd edition. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

BACK TO TOP ↑

Unit 13: Look Down for Hope – Phytoremediation in an Italian Steel Town

This section considers the practice of phytoremediation as both a model and source of inspiration for radical hope. It takes as a case study the city of Taranto, in southern Italy. Taranto has long been devastated by the effects of toxic emissions, including high levels of dioxins, from the massive Ilva steel plant. Classified as Persistent Organic Pollutants, dioxins and dioxin-like compounds are almost imperceptible, remaining largely undetected by the unaided human or animal body where they can lead to illnesses including cancer, digestive disease and thyroid imbalance. Dioxins travel by water and air, bioaccumulate in food chains and living tissues, and thus encourage a reckoning with trans-corporeality, the “material interconnections of human corporeality with the more-than-human world” (Alaimo, 2010: 2). In recent years residents, activists and artists have banded together in Taranto and surrounding areas to combat local dioxins with a very different and yet equally transmutable, potentially transcorporeal, organic substance: hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) Through both agricultural and artistic practice, Taranto’s contemporary narrators seek to convey the potential of hemp as a detoxifying salve and means of regeneration for land, artisanal community and local economy. They promote hemp as a natural tool for phytoremediation – the use of living plants to detoxify soil and water – and as an easily cultivated crop capable of providing fiber for textiles, ceramics and more, thus reinvigorating traditional forms of productive craftsmanship. In this they frame hemp as an anti-dioxin: purifying rather than toxic and so manifestly perceptible in its overt and multi-form physicality. Their work is profoundly hopeful, and radically simple, in its premise: that a plant can simultaneously diminish toxins within the soil on which so many lives depend, and that the fiber it produces might offer an alternative model for forward growth in a community and landscape otherwise devastated by large-scale industrial production.

How do you define radical hope?

I see “radical hope” as the purest type of hope: a deep and unshakeable belief that something positive can happen despite difficult circumstances. It is a dynamic hope often backed by actions that may run counter to apparent restrictions.

How do you see radical hope emerging or playing out in your case study?

The current situation in Taranto regarding environment, health, and employment is brutal. The massive Ilva steelworks produces approximately 90% of Italy’s annual dioxin output; farmers can no longer cultivate crops or raise feed animals within 15 kilometers of the centrally located steelworks; residents face excessive rates of cancer, lung and digestive diseases, and perinatal illness; and many Ilva workers feel they have no choice but to trade unsafe working conditions and eventual illness for a paycheck. More and more area residents, current and former Ilva workers, and environmental health advocates are lobbying for permanent closure of the steelworks, but the Italian government continues to declare that Ilva will remain open.

Should you visit the waterfront city, you might notice a fine coating of red steel dust on stationary surfaces; the blast furnaces dominating the skyline just beyond the centrally located Tamburi neighborhood, where children have been forbidden to access playgrounds in recent years; significant abandon and disrepair in the historic old town; and talk of tumors and unemployment at local bars. But you will also encounter a nascent (re)generative energy: artists, folklorists, activists and cultural operators of all sorts have begun to re-occupy neglected spaces for their creative practices, often emphasizing natural materials from land and sea alongside local artisanal tradition. Many incorporate hemp – from the artist collective Ammostro, who use the fiber in their screen-printing studio, to the socially engaged artist Noel Gazzano, who planted hemp seeds as part of her 2016 performance piece “The Unbearable Condition,” to the Fornaro family, who cultivate the plant on their large family farm directly next to Ilva grounds, seeking to simultaneously detoxify the soil and provide sustainable fiber and grain. That they take on such initiatives in the face of a massive industrial giant, and a massive crisis of both environment and economy, demonstrates the deep faith, long-term vision and empowered agency inherent to radical hope.

Readings/Resources

- Alaimo, Stacy. Bodily Natures: Science, Environment and the Material Self. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010.

- Barca, Stefania & Emanuele Leonardi. “Working-class ecology and union politics: a conceptual topology,” Globalizations, 15:4 (2018): 487-503.

- Fisher-Lichte, Erika. The Transformative Power of Performance: A New Aesthetics. Translated by Saskya Iris Jain. London: Routledge, 2008.

- Gutterman, Lila. “Back to Chernobyl,” New Scientist. No. 2181. 10 April 1999.

- Linger, P., Ostwald, A. & Haensler, “Cannabis sativa L. growing on heavy metal contaminated soil: growth, cadmium uptake and photosynthesis.” J. Biol Plant (2005) 49: 567-576.

- Lonely Planet, “Taranto,”

- Lucifora, A., Bianco, F., and Vagliasindi G.M. Environmental and corporate mis- compliance: A case study on the ILVA steel plant in Italy. Study in the framework of the research project. Catania: University of Catania, 2015.

- Mitchell, WJT. Landscape and Power. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

- Rodrìguez, Àlvaro Ivàn Hernàndez, “Where Can Walking Be Taking Me?” in Sentient Performativities of Embodiment: Thinking Alongside the Human. Edited by Lynette Hunter, Elisabeth Krimmer and Peter Lichtenfels. London: Lexington, 2016. 195-204.

- Seger, Monica. “Toxic Tales: On Representing Environmental Crisis in Puglia,” in Encounters With the Real in Contemporary Italian Literature and Cinema, Edited by Pasquale Verdicchio & Laura Di Martino. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017. 29-46.

- Seger, Monica. “Thinking Through Taranto: Toxic Embodiment, Eco-catastrophe and the Power of Narrative.” In Landscapes, Natures, Ecologies: Italy and the Environmental Humanities, Enrico Cesaretti, Serenella Iovino and Elena Past, eds. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2018. 184-193.

- Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

- United Nations Environment Programme, Newsletter and Technical Publications Freshwater Management Series No. 2 Phytoremediation: An Environmentally Sound Technology for Pollution Prevention, Control and Redmediation: An Introductory Guide To Decision-Makers

- On the Fornaro family farm

- Phytoremediation: An Environmentally Sound Technology for Pollution Prevention, Control and Remediation An Introductory Guide To Decision-Makers

- Farmers in Italy fight soil contamination with cannabis

- Artist Noel Gazzano

BACK TO TOP ↑

Unit 14: Living In Good Relation with the Environment: A Syllabus of Radical Hope

Alina Scott

Description This syllabus emerged from a conference course with one of the initial Radical Hope contributors and organizers, Dr. Erika Bsumek. Each week featured readings from already submitted syllabi now available on radicalhopesyllabus.com.

While it began with the intention to test the usefulness of each syllabus and case study across disciplines, I quickly found more and more overlap as the weeks progressed. Each author brought their own set of influences to the discussion of radical hope, the RH syllabi quickly formed a cohesive whole. My experience is a testament to both the usefulness of this tool and the importance of it being taught in classes wishing to touch on topics related to the environmental humanities.

My section of the syllabus is a result of the readings I’ve completed for this course, my own understanding of radical hope, and how I have come to understand the readings and individuals who contribute to the discussion of maintaining radical hopefulness accompanied by action, in the face of environmental degradation, catastrophe, and despair.

How do you define radical hope? I’d define radical hope as a conscious effort to acknowledge the degradation of culture or environment, secondly, a willingness to educate oneself and others, and finally, a belief in the humanity and the application of sustainable environmental practices. Radical hope requires some level of thinking beyond the present, acknowledging the failures and successes of the past, and being open to the action that knowledge demands.

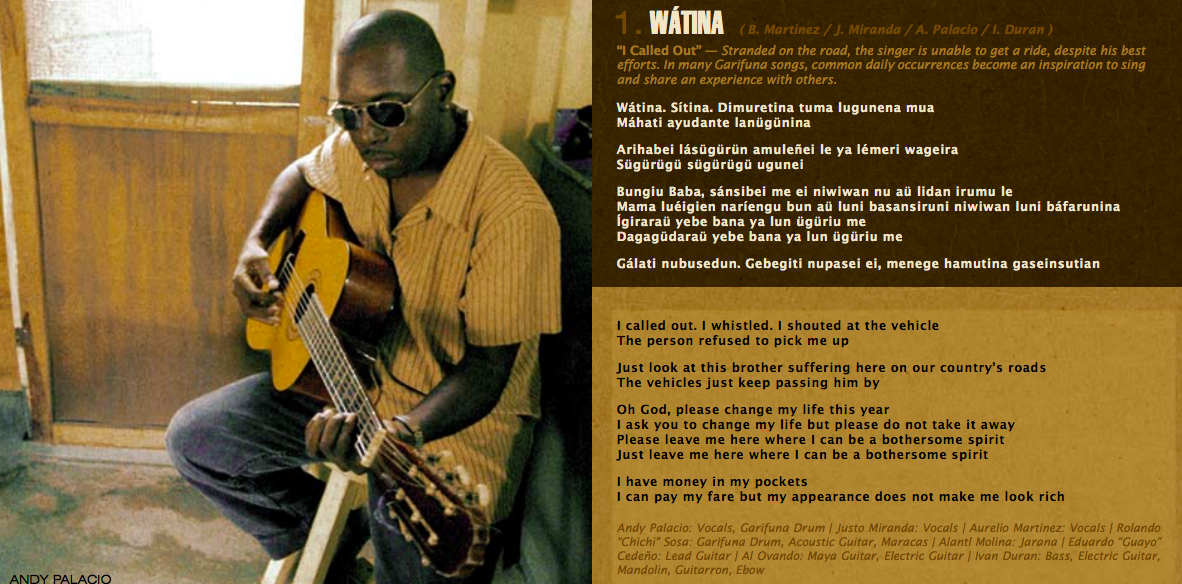

Jonathan Lear’s Radical Hope (2006) opens the door to the discussion of vulnerability and ethics in the face of cultural devastation. The vulnerability facing the Crow Nation featured in Lear’s work can be applied to broader discussions of environmental degradation and change that is often accompanied by despair. Rather than dwell in despair, Carsten Wergin suggests respectful and careful listening to others. I’d like to suggest turning our ears toward the Garifuna in Belize as the representation of radical hope and persistence.

How do you see radical hope emerging or playing out in your case study? The Garifuna are mixed-race descendants of West African, Central African, Island Carib, European, and Arawak people. Persecution led them to island hop until they settled along the Caribbean Coast in Honduras, Belize, Guatemala and Nicaragua. Facing persecution in the lands they now inhabit, and often bearing the brunt of environmental change, overfishing, and overpopulation, Garifuna peoples are also advocates of change (See Andy Palacio and the Garifuna Collective: Watina, “Net Loss: Are We Drowning our Future?”, Cayetano’s “Drums of My Fathers”)

REQUIRED READINGS

Social

- Hashtags: #OceanOptimism #RadicalHope

- Follow GreenMatters, Oceana, Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society

- Radical Hope Twitter List

Media

- On Healing: Queer Eye, Season 2, Ep. 1 “God Bless Gay”

- Radical Hope Music Playlist

- The Lorax (1972)

- DamNation Film (2014)

- Kiki (2017)

- Carsten Wergin (2017) “How Can Australian Indigenous Experience Change Western Perspectives of the World?” Latest Thinking. LT Video Publication, DOI: https://doi.org/10.21036/LTPUB10513

- “Net Loss: Are We Drowning our Future?” Oceana.

- Alex Elle’s Hey Girl Podcast

- Media Indigena Podcast

Poetry

- Layli Long Soldier, “WHEREAS: Poems”

- Marvin Gaye’s 1971 album – What’s Going On

- Andy Palacio and the Garifuna Collective- Watina (Lyrics and Video)

- Drums of My Fathers, Roy E. Cayetano.

Literature

- Roberson, Jehan. “Towards The Black Girl Future”

- Garsd, Jasmine. “Garifuna: The Young Black Latino Exodus You’ve Never Heard About.” Splinter. July 24, 2017.

- Sweeney, James L. (2007). “Caribs, Maroons, Jacobins, Brigands, and Sugar Barons: The Last Stand of the Black Caribs on St. Vincent”, African Diaspora Archaeology Network, March 2007.

- On Place, Land, and Meaning:

-

- Bsumek, Erika Marie. Nation-States and the Global Environment: New Approaches to International Environmental History. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Farmer, Jared. On Zion’s Mount: Mormons, Indians, and the American Landscape. Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Farmer, Jared. “Glen Canyon and the Persistence of Wilderness.” The Western Historical Quarterly 27, no. 2 (1996): 211-22. doi:10.2307/970618.

- Radical Hope & Place:

- Lear, Jonathan. Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2006.

- Basso, Keith H., 1940-2013. Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language among the Western Apache. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996.

-

-

- I’d recommend reading Lear and Basso’s books together.

-

- Hope

- Higgins, Maeve. “Meet the Inspiring, Hopeful Women Fighting for Climate Justice | Maeve Higgins.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 24 July 2018.

- “Belize Praised for ‘visionary’ Steps to save Coral Reef.” BBC News. June 27, 2018.

- Klein, Naomi “Capitalism Killed Our Climate Momentum, Not “Human Nature”.” The Intercept. August 03, 2018.

- Solnit, Rebecca. Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities. New York: Nation Books, 2004.

- An Inspiration Board for 2018 & A “Friend-Sourced” Syllabus

- Encyclical Letter Laudato Si’ Of The Holy Father Francis on Care for our Common Home

- Hope That Warrants Action:

- Doom and Gloom: An Exploration through letters

- Erika Bsumek and Betsy Frederick Rothwell, “Stop Trying to Control Nature,” Time Magazine, April 22, 2016.

- Dana Powell, Landscapes of Power: Politics of Energy in the Navajo Nation (Duke University Press, 2018)

- Nick Estes. “Fighting for Our Lives: #NoDAPL in Historical Context.” Therednation.org. February 18, 2017.

- Alastair McIntosh (2004), Soil and Soul: People Versus Corporate Power (Aurum Press)

BACK TO TOP ↑

Unit 15: On Love and Property

Kara Thompson