John Barry

WB Yeats, ‘The Lake Isle of Innisfree’

I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made:

Nine bean-rows will I have there, a hive for the honey-bee;

And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping

slow,

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket

sings;

There midnight’s all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet’s wings.

I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart’s core.

Hope Is The Thing With Feathers, Emily Dickinson

‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers—

That perches in the soul—

And sings the tune without the words—

And never stops—at all—

And sweetest—in the Gale—is heard—

And sore must be the storm—

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm—

I’ve heard it in the chillest land—

And on the strangest Sea—

Yet, never, in Extremity,

It asked a crumb—of Me.

In the turbulent times we live in and the uneven and unjust production and experience of social, economic and ecological harms, hope in all its manifestations is both available (if we look hard enough for it) and much needed.

How do you define radical hope?

The inspiration behind this workshop, and my own interest and work on ‘radical hope’ is based on that concept which came across almost a decade ago when I first read Jonathan Lear’s remarkable book, Radical Hope. In that book, Lear outlines a peculiar human vulnerability, one which all papers touch upon in different ways. As Lear puts it

“We seem to acquire it [this vulnerability as a result of the fact that we essentially inhabit a way of life. Humans are by nature cultural animals: we necessarily inhabit a way of life that is expressed in a culture. But our way of life –whatever it is– is vulnerable in various ways. And we, as participants in that way of life, thereby inherit a vulnerability. Should that way of life break down, that is our problem” (2006: 6).

This leads him, and us, to a troubling existential blind spot within (most) human cultures “the inability to conceive of its own destruction and possible extinction” (2006: 83). This means, for example, that we do not typically prepare our younger generation to consider or to prepare for the possible eventuality of our way/s of life, the terms and practices we use to render such ways of life, of common goods etc. to be vulnerable, so vulnerable they might, someday disappear completely. This ‘ontological insecurity’, to paraphrase Anthony Giddens, is not something we usually or usually willingly do. It is speculative (it may not happen, so why worry about it?), it is worrying and disturbing – hence thinking about possible futures might compromise one’s enjoyment of their present), and even if there are troubling times ahead human ingenuity, improvisation and resilience coupled with technological innovation will ‘take care of it’. Radical hope for me is not the same as optimism. As Vaclav Havel so perceptively put it “Hope is definitely not the same thing as optimism. It is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out”.

In this way ‘radical hope’ is a clear eyed recognition of the problems we face, a courageous and explicit disavowal of the temptations of a naïve (and at times dangerous) assumption that ‘all will be well’, but nevertheless a belief in the capacity of human agency. Hope, as Emily Dickinson, put it “is the thing with feathers”. Or as Lear notes, “What makes this hope radical is that it is directed toward a future goodness that transcends the current ability to understand what it is. Radical hope anticipates a good for which those who have the hope as yet lack the appropriate concepts with which to understand it” (2006: 103).

How do you see radical hope emerging or playing out in your case study?

Politically, my main area of interest and concern, there is much work to be done in establishing a critical, inspiring and realistic ‘infrastructure of hope’ which I view as allowing for a dialogue around new ideas about we organise the economy, conceive of a ‘good life’, reconfigure our democratic politics and so on. In the realm of ideas and the politically feasible there is a crying need for unleashing creativity and rethinking and repurposing established ways of ideas, practices and frames of reference. Our crisis is as much a crisis of creativity as it is a crisis of capitalism, the decline in a belief in collective change, climate change and so on. Such a creative dialogue to establish an ‘infrastructure of hope’ calls for public i.e. political debate and hybridisation and interdisciplinary cross-pollination between science, technology, philosophy, ethics, with participants from faith communities, those of no faith, citizens, experts, civil servants, business, trades unions, teachers, academics and students and many more besides. In short, radical hope and the creation of an infrastructure of hope may call for something akin to a new Renaissance or Enlightenment. A new Enlightenment however based more on modesty and critical self-reflection than the often bullish and arrogant anthropocentrism of ‘the Anthropocene’. Radical hope in our turbulent times I would suggest calls us to reflect less on how we as a species can control or manage the planet, to ‘take hold of the tiller of creation’ as Teilhard de Chardin put it. Perhaps it calls us to manage that for which we need no new technology or science, to manage not the planet or the more that human world, but rather to manage our relationships (both material-metabolic, conceptual and moral) with the earth, its entities and processes. And, while the reappraisal of our relationships is a quintessentially political act, and thus ‘radical’ in the Latin sense of ‘getting to the root’ of the problem, the sense of hope outlined here is radical in another sense.

This is the sense of hope as an antidote to the dangers (or comforting temptations) of what can be a debilitating negativity in forensically detailing all the problems of the current time. Hope here is a virtue guarding against the political and intellectual vice of dwelling in a self-righteous negativity, to ‘curse the dark’ but without also ‘lighting a candle’ for fear of being seen (or self-regarded) as naïve, politically or ideologically motivated or even ‘utopian’. Here what makes this hope radical is in the sense that Raymond Williams so aptly put it:

“To be truly radical is to make hope possible,

rather than despair convincing”.

Readings:

- Sharon Astyk (2008), Depletion & Abundance: Life on the New Home Front (New Society Publishers).

- Vaclav Havel (1985), The Power of the Powerless (London: Routledge).

- Vaclav Havel (1986), Living in Truth (London: Faber and Faber).

- Rob Hopkins (2008), The Transition Handbook: From Oil Dependency to Local Resilience (Totnes: Green Books).

- Gerry O’Hanlon SJ (ed) (2017), A Dialogue of Hope: Critical Thinking for Critical Times (Dublin: Messenger Publications).

- Pope Francis (2015), Laudato ‘Si: Care for our Common Home, available at: http://w2.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20150524_enciclica-laudato-si.html

- Jonathan Lear (2008) Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation (Harvard University Press).

- Alastair McIntosh (2004), Soil and Soul: People Versus Corporate Power (Aurum Press)

- Susan Sontag (1978), Illness as Metaphor, (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux).

- Raymond Williams (1989), Resources of Hope: Culture, Democracy, Socialism (London: Verso).

- The poetry of William Butler Yeats and Padraig Kavanagh

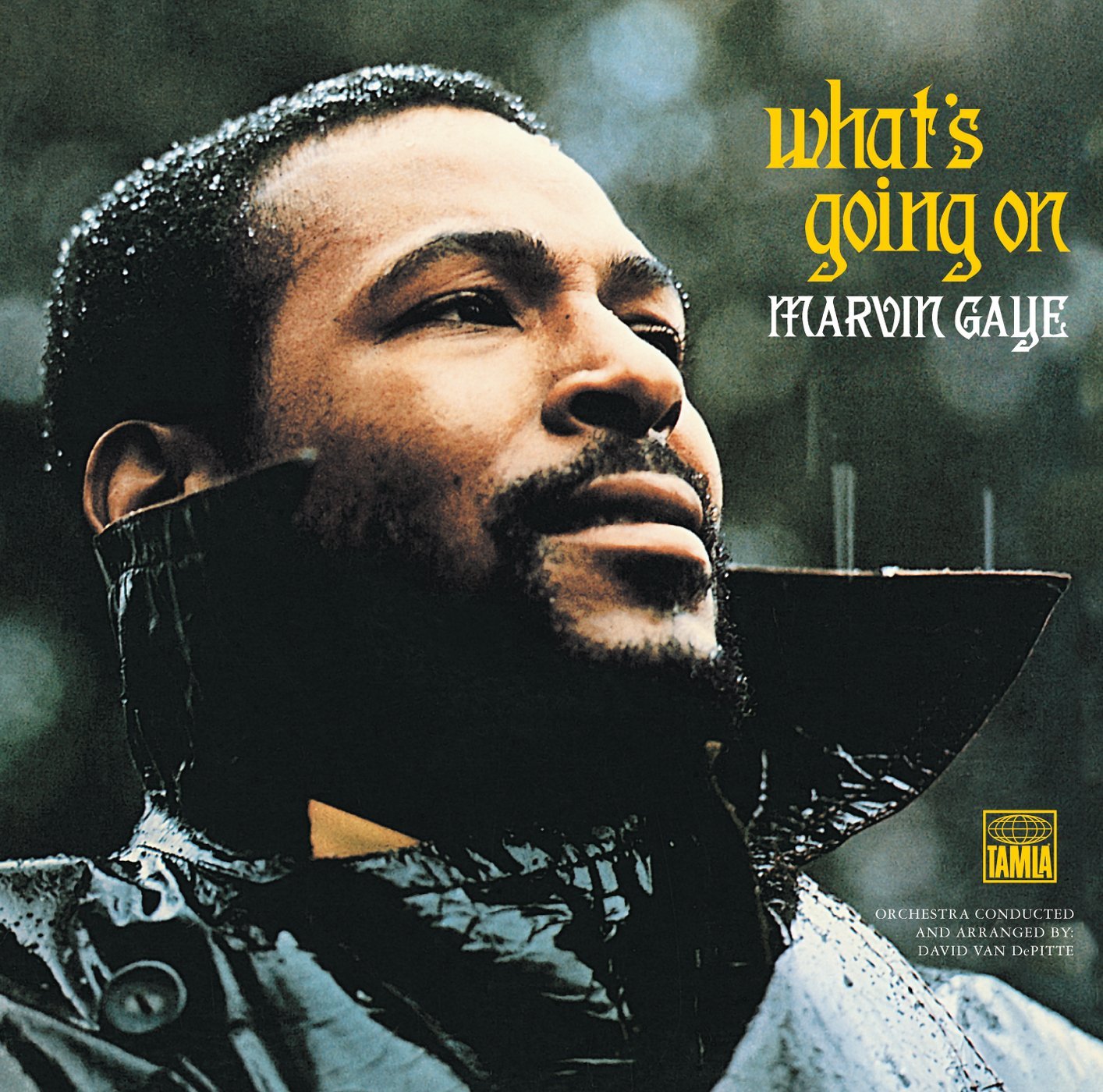

- Marvin Gaye’s 1971 album – What’s Going On

- Henryk Górecki’s Symphony No. 3: Symphony of Sorrowful Songs

- Dr Seuss’ The Lorax,